Tag-A-Giant Q&A

How long has Tag A Giant been around?

TAG-A-Giant is currently in its 25th year. TAG was founded by Stanford and Duke University scientists, alongside interested fishers. Our goal is ensuring the future of pelagic fish such as Atlantic and Pacific bluefin tunas (www.tagagiant.org) by collecting the science needed to support management initiatives.

What species of bluefin have you tagged?

We have tagged all three species of bluefin tunas. Atlantic bluefin (Thunnus thynnus), Pacific bluefin (Thunnus orientalis), and Southern bluefin (Thunnus maccoyii). Our primary focus is Northern bluefin tuna, but we also tag other species of tunas, billfishes, sharks, mantas, and sea turtles.

What are the goals of the program/why was it started?

TAG was founded to bring fishermen, scientists, fisheries managers, and funders together to generate new knowledge on fish that were both recreational and commercially of interest - We started tagging Atlantic bluefin tuna and expanded quickly to Pacific bluefin. We continued tagging other pelagic species (fish and elasmobranchs) around the globe. Working alongside three North American companies, we also helped to develop and trial the electronic tags (Pop-up satellite archival and internal archival tags, as well as the first shark fin tags called SPOT) deployed on fish today. Our lab also worked on the mathematics of estimating positions with light and oceanographic data collected on the tag to map the spatial and temporal habitat of the fish. Our lab utilizes advanced genetics to look at population structure, and we look at the physiology/biochemistry of these unique species to understand niche preferences/tolerances. We have just finished the genomes of Atlantic and Pacific bluefin at a very concise level.

The science is not only published in peer-reviewed journals but presented to both domestic and international fisheries managers so they can incorporate the data into models on the status of the fishery.

What’s been the most exciting part of the program?

We are at the cutting edge of scientific technology. Since the first electronic tags to the new generation of tags (pop-up satellite, archival, camera tags), we are finding new ways to “peel back the ocean.” The technology, combined with genomics and isotopic data are at the forefront of the tuna, billfish and elasmobranch knowledge. The data will help empower better management of these fisheries.

What does a day in the life on an expedition look like?

We have tagged over ~3000 tunas, 1300 sharks, ~450 billfishes and ~100 mantas. To do this successfully requires enormous logistical coordination and countless hours of preparation prior to the trip. This begins at the lab with programming and leadering of tags, as well as ordering and packing equipment. Like a good fisher, we create terminal tackle tethers for the tags that helps keep them on the fish.

Then, just like a typical fishing trip we must book travel arrangements for researchers, prepare the equipment and electronic tags, hire vessels and crew...and most importantly find a weather window when the fish are biting!

TAG science succeeds because we collaborate with the best fishers in the world. It’s the team approach that has led to our success.

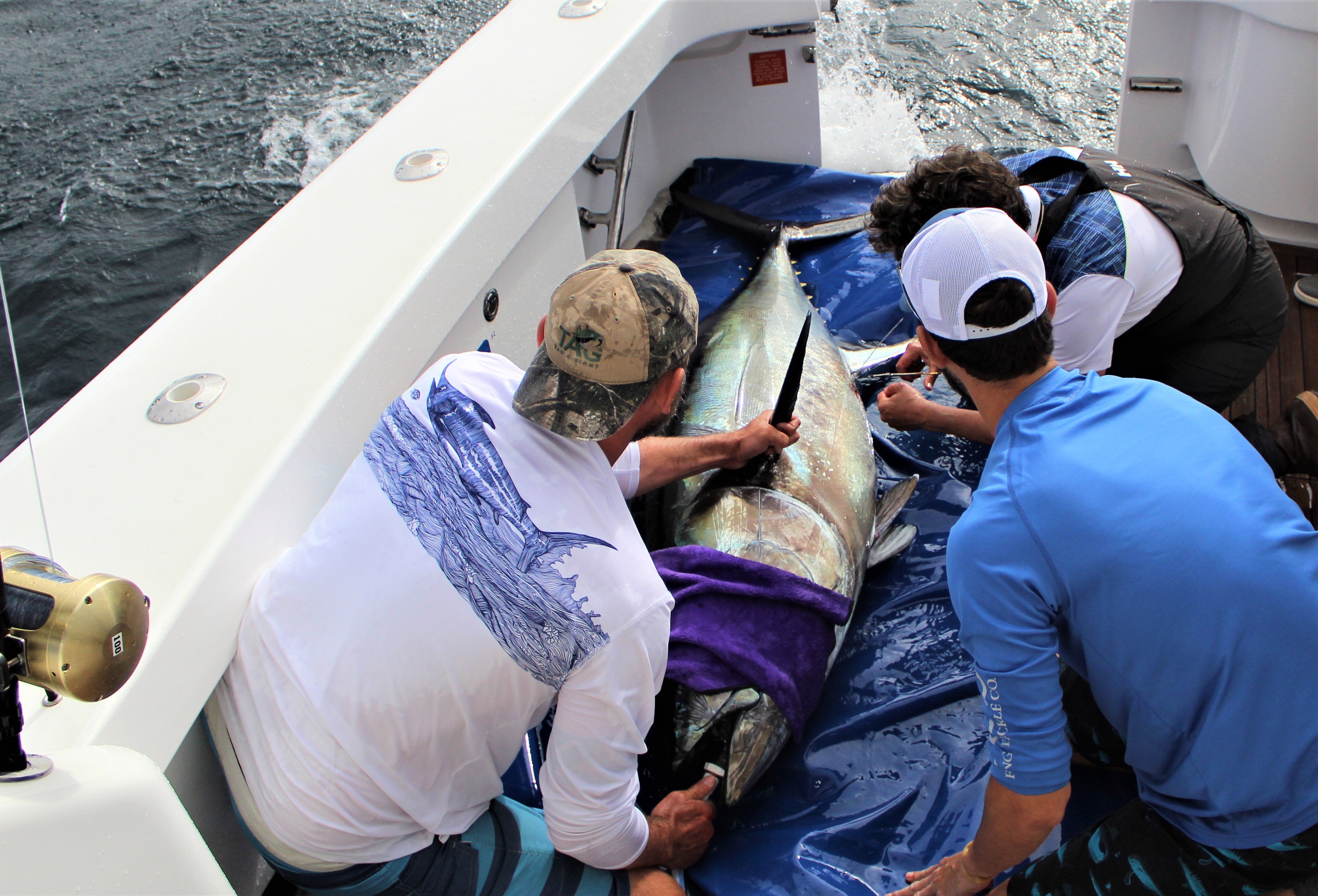

A single day is much like any day fishing; our scientific team ensures tags are ordered, numbered, and recorded. We follow a strict scientific protocol prior to attachment or surgical procedure to ensure the health of the animal, so instruments/tags are cleaned and sterilized.

Then like all fishers, we head out to the open sea and if we are lucky enough to catch our targeted species, we use techniques our program has developed to bring fish on board the boat, tag them and let them go. The tagging and retention of the scientific instrument requires unique attachment tethers and precision placement. The electronic tags are between $1,500-$5,000 each, and depending on the tag, can record data up to 7 years.

What have been the greatest successes of the program?

In the mid-90s, TAG worked alongside engineers from various tag manufactures to develop the electronic tags we use today. The development of the right type of tag for each animal (tuna, shark, billfish) has been critical to the Tag-A-Giant campaign over the last couple of decades. We are innovators and are proud of our capacity to achieve long term attachments and deployments (Up to 6 years on a bluefin!).

The deployment of more than 2,000 archival tags on tuna in the Pacific during the Tagging of Pacific Pelagic/Census of Marine Life program catapulted electronic tagging into the forefront of ocean ecology.

Our science helped to create protections for spawning fish in the Gulf of Mexico. This was encouraging as it showed that electronic tagging science in collaboration with NGOs and government could be used to protect the species when it was most vulnerable.

Our Great Marlin Race in collaboration with the IGFA has utilized citizen scientists to tag over 450 marlin around the globe producing a trove of scientific data.

We have tagged over 3,000 bluefin tuna off numerous coasts from the US (both Atlantic and Pacific) to New Zealand, Australia, Taiwan, Japan, Canada, Ireland, England, Wales, Morocco, Spain, Italy, Portugal, Israel, and to see the bluefin population explode in the last couple of years is a testament to good management, bluefin resilience and great science. There are plenty of questions to be answered. The population increases could be echoes of strong recruitments in certain year classes, or it could be environmental factors aggregating fish, but there are positive signs of a global bluefin tuna recovery.

We are working with ICCAT to build more accurate models for fisheries that include the biology we obtain from tagging and genetics.

The challenge with fisheries management is that we can’t peel back the ocean and count the fish, however these tags and genetics give us new tools to estimate populations.

What have been the biggest wins to you personally?

The ongoing recovery of bluefin in the Atlantic, and the ability to see where bluefin go for up to six years under the sea. Such a long track was something we only dreamed about when TAG was first founded.

We are also creating the next generation of scientists and advocates for tuna, billfish and shark. This may be our greatest legacy. We have had University students from Stanford & across the world work with our team. Some are on the forefront of fisheries science and management now. We have also edited two books on tunas and published 200 plus scientific papers all intended to incrementally help to build the knowledge base for sustainable fisheries!

What’s your best memory working with the program?

Off the coast of North Carolina, we electronically tagged almost 40 bluefin tuna in one day with the help of almost 50 boats…so amazing to see the whole community involved! Similarly, we tagged over 100 bluefin on the Shogun on one trip in a few days, and hand feeding 1,000 lb. giants in Nova Scotia is second to none!

How can our community get involved and support the mission?

Fishers can sponsor a satellite or archival tag or donate time fishing with our team (Charters). We allow sponsors on many trips.

Why is the bluefin an important species to tag and learn more about?

Northern bluefin tuna are iconic fish. Large, powerful, warm-bodied and for tunas, long-lived with billion dollar fisheries- sought after by fishers across the globe. They are now regulated by strict quotas to ensure their recovery. The giant bluefin is one of the greatest sports fishing challenge – and we hope that we can recover the northern bluefin in both oceans as they are vital to their ecosystems

What more is there to learn about the species to better conserve them?

In the Atlantic, the bluefin tuna population structure is increasing in complexity.

How many years of tagged data have been analyzed?

25 years